The Economics of Grand Slam Tournaments: How Much Do Players Outside the Top 10 Earn

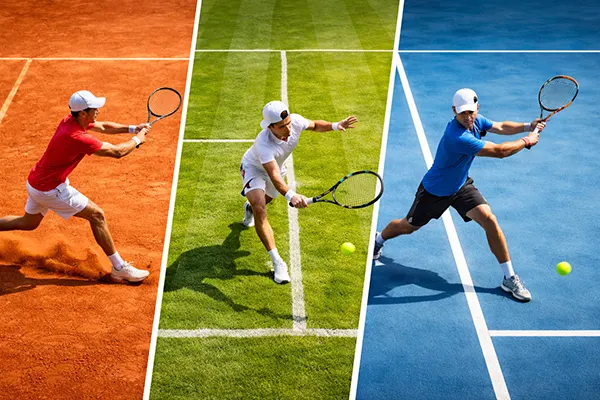

Grand Slam tournaments remain the ultimate stage for tennis professionals, representing both athletic prestige and financial opportunity. However, while the top-ranked stars capture the bulk of global attention and prize money, the majority of professional players operate under vastly different economic realities. In 2025, the growing discussion around income inequality in tennis has drawn attention to the struggles and sustainability of life on tour for those ranked outside the top 10.

Prize Money Distribution in Grand Slam Events

Each of the four major Grand Slam tournaments – the Australian Open, French Open, Wimbledon, and the US Open – now offers record-breaking prize pools exceeding £45 million. Despite this growth, the distribution of winnings remains heavily skewed toward the highest achievers. A Grand Slam champion in 2025 earns approximately £2.3 million, while players losing in the opening round receive around £55,000. On paper, this seems fair, yet when travel, accommodation, taxes, and coaching expenses are deducted, the profit margin for lower-ranked players becomes significantly narrower.

The median player ranked between 50 and 100 in the world can expect to earn roughly £700,000 annually, but only a small fraction comes from Grand Slam events. For those ranked outside the top 100, annual prize money often falls below £200,000 — an amount that barely covers season-long expenses on the ATP or WTA circuits. Many players rely on smaller tournaments and national federations for financial support.

Even though tournament organisers have increased early-round payouts, this has not solved the broader issue of inequality. The cost of maintaining a professional career — including coaching, physiotherapy, equipment, and travel — continues to rise, leaving a majority of athletes operating on minimal margins.

Economic Impact Beyond Prize Money

For lower-ranked tennis players, sponsorships and endorsements provide limited relief. While the world’s top 10 can earn tens of millions annually from brand partnerships, players outside the spotlight often receive small equipment deals or bonuses tied strictly to tournament performance. The contrast illustrates how global visibility drives commercial success far more than athletic potential.

Many players outside the top 100 also turn to local leagues or exhibition matches to supplement their income. These short-term contracts, particularly in countries with strong tennis cultures such as Germany, France, and Japan, can help stabilise earnings during the off-season. However, they are rarely sufficient to guarantee financial security.

To address this imbalance, player councils and governing bodies have proposed adjustments to Grand Slam revenue sharing. Some initiatives, such as travel grants and guaranteed base payments for early-round participants, are already in motion. Still, the gap between elite and mid-level players remains a defining feature of modern tennis economics.

The Cost of Competing at the Top Level

The financial commitment required to stay competitive on the ATP and WTA tours is immense. Players typically spend between £100,000 and £250,000 per season covering coaching, physiotherapy, travel, and equipment. Those ranked beyond the top 100 often struggle to sustain this investment, leading some to take on part-time roles as coaches or club professionals during off-weeks to remain financially afloat.

In 2025, the average cost of a professional tennis career has risen due to inflation and higher global travel costs. Despite the record prize money offered by major tournaments, most lower-ranked players must rely on Challenger and ITF events for consistent income — yet these competitions offer minimal financial reward, often less than £10,000 for a title win.

This economic imbalance highlights the sport’s dependency on top-tier stars for financial sustainability. Grand Slam organisers continue to face growing pressure to ensure that the sport’s wealth reaches the broader player base, sustaining future generations of professional athletes.

Financial Sustainability for Lower-Ranked Players

As discussions around fair compensation gain traction, governing bodies such as the ATP, WTA, and ITF have begun experimenting with structured financial support systems. Examples include minimum wage guarantees for tour participants and enhanced pension schemes for retiring professionals. These measures are designed to create a more balanced and sustainable ecosystem.

However, the implementation of such initiatives varies across tournaments and federations. While the US Open has taken the lead with transparent redistribution models, other Grand Slam organisers are slower to adopt similar strategies. The result is a fragmented system where financial stability still depends largely on nationality, sponsorship access, and ranking.

In the long term, reforms in revenue allocation, digital streaming income, and athlete representation could redefine tennis economics. For now, though, the financial divide between stars and journeyman players remains a defining feature of the professional tour — a reality that challenges the inclusivity and fairness of the sport.

The Future of Financial Equality in Tennis

Looking ahead to the next decade, there is growing optimism that structural change could reshape professional tennis. The rise of collective bargaining initiatives, led by the Professional Tennis Players Association (PTPA), has opened dialogue on fairer compensation and better working conditions for players across all rankings.

Moreover, the increasing commercialisation of digital streaming and betting rights has created new revenue streams. If managed transparently, these could fund long-term stability initiatives for lower-ranked professionals. The challenge lies in ensuring equitable distribution rather than concentrating benefits among a few elite organisers and sponsors.

The success of tennis as a global sport ultimately depends on the health and motivation of its entire player base. Recognising the financial struggles of those outside the top 10 is not merely a matter of fairness — it is an investment in the sport’s future sustainability and diversity.

Toward a More Inclusive Tennis Economy

Efforts to close the income gap in professional tennis continue to evolve in 2025. Collaborative projects between players, federations, and event organisers aim to redesign the economic framework of the sport. These discussions include transparent budget reporting, redistribution of broadcast revenues, and funding programs for emerging talents.

Furthermore, Grand Slam events are increasingly under public scrutiny to demonstrate social responsibility. Fans, journalists, and advocacy groups argue that supporting lower-ranked athletes aligns with tennis’s broader mission to remain a meritocratic and inclusive sport. As the global audience grows, so too does the demand for fairer competition both on and off the court.

While true parity may still be years away, progress is measurable. The ongoing reforms suggest that by 2030, professional tennis could achieve a more balanced economic structure — one that rewards effort, perseverance, and contribution, not merely ranking position.